At the east end of Carnegie Mellon University’s campus, two newly installed public artworks offer students the chance to engage with their history and the ongoing story of CMU.

They say time reveals all. For artist Guadalupe Maravilla, whose Descansa Espíritus/Rest Spirits now hangs in the Highmark Center for Health, Wellness and Athletics, and artist Amanda Ross-Ho, whose Untitled Core Sample (THE FENCE) stands outside of the Forbes Beeler Apartments, time is both a medium and a message.

Descansa Espíritus/Rest Spirits by Guadalupe Maravilla

“There’s something called generational trauma that can be passed on,” said Maravilla, who conceived of his sculpture as an offering to the ancestors of students seeking healing and training inside the center. “When I had cancer, I was doing a lot of meditation, and I kept getting messages that in order for me to heal fully, I had to heal seven generations back and seven generations forward. So a lot of the work that I’m doing revolves around not only healing myself, but healing my family, healing my communities.”

Past and future are present throughout Maravilla’s autobiographical practice, which often involves ceremonies to activate his installations. “It’s really important to talk about my ancestors, because they protect me,” he said. Maravilla, who is based in Brooklyn, arrived in the United States as an unaccompanied minor fleeing El Salvador’s civil war in 1984. His journey took another turn when he was diagnosed with cancer 12 years ago, an experience that has continued shaping his focus on themes of trauma and healing. “For me, it’s really important to create a new symbol of wellness, of healing, of rest. And I believe the hammocks do that.”

Installed in October, Maravilla’s sculpture comprises six polished aluminum hammocks suspended into a symmetrical mobile. Each mirrors the full-scale dimensions of a single-person cloth hammock, inspired by the traditional Central American hammocks Maravilla grew up with. Soaring above the building’s central stairwell, the sculpture responds to the glass wall it faces, seemingly changing throughout the day as light and shadow shift. Maravilla selected the position because, here, the sculpture exists within all three stories of building, yet floats just out of reach. “When I use hammocks in my work, they’re never low enough so someone can touch them,” he said. “They’re high because they’re intended for the ancestors to take a rest. I believe that our guardian angels, our spirits and our ancestors, also need a break.”

Top: Photos by Tom Little. Bottom: Courtesy of UAP

Untitled Core Sample (THE FENCE) by Amanda Ross-Ho

Exploring another form of collective history, Ross-Ho’s sculpture memorializes countless layers of paint from The Fence — a CMU landmark that students have been painting since 1923. This irregular, stratified column, installed this May at a heavily trafficked end of Forbes Avenue, recreates a five-inch cylindrical core sample of the structure on a massive scale and with forensic precision, in a process that took over two years to complete. “Ironically, the time making things about time is slow,” Ross-Ho said. After a series of steps involving both high-tech methods and traditional casting techniques, the most painstaking stage came down to a trompe-l’oeil specialist, who sprayed the bronze cast with automotive solvent paints at UAP, where the sculpture was produced. “A lot of people along the way had different ideas about how we might accomplish this,” Ross-Ho explained. “One idea was to have individual discs of metal stacked on top of each other, for example. The problem with that, for me, is that it becomes an interpretation rather than a portrait.”

Ross-Ho, who is Professor in the Department of Art at UC Irvine, draws on extensive archival research in her practice, including hundreds of photos from the CMU libraries and two informal interviews with her mother and her mother’s best friend, who met as first-year students at CMU in the 1960s. “I was very interested from the beginning in making something that would be by students, for students,” she said. Anyone who painted The Fence in the last 30 years, after the original wood structure collapsed under the weight of decades of paint and was replaced by steel and concrete in 1993, can attempt to find their layer in sculpture.

The coincidence of the core sample being extracted in 2023, during The Fence’s centennial year, makes the sculpture symbolic well beyond the decades physically represented — whether or not many will immediately recognize it. “Amanda’s work is this vibrant, wild, very weird object that, at first, people don’t know how to respond to,” said Elizabeth Chodos, the University’s Public Art Curator, who also serves as an Associate Professor in the School of Art and Director of the Miller ICA (soon to become ICA Pittsburgh). “There’s this momentary confusion, and then the a-ha moment of realizing, wow, this is an exact replica of a core sample of thousands of layers of paint, and all the hands that have been a part of it.”

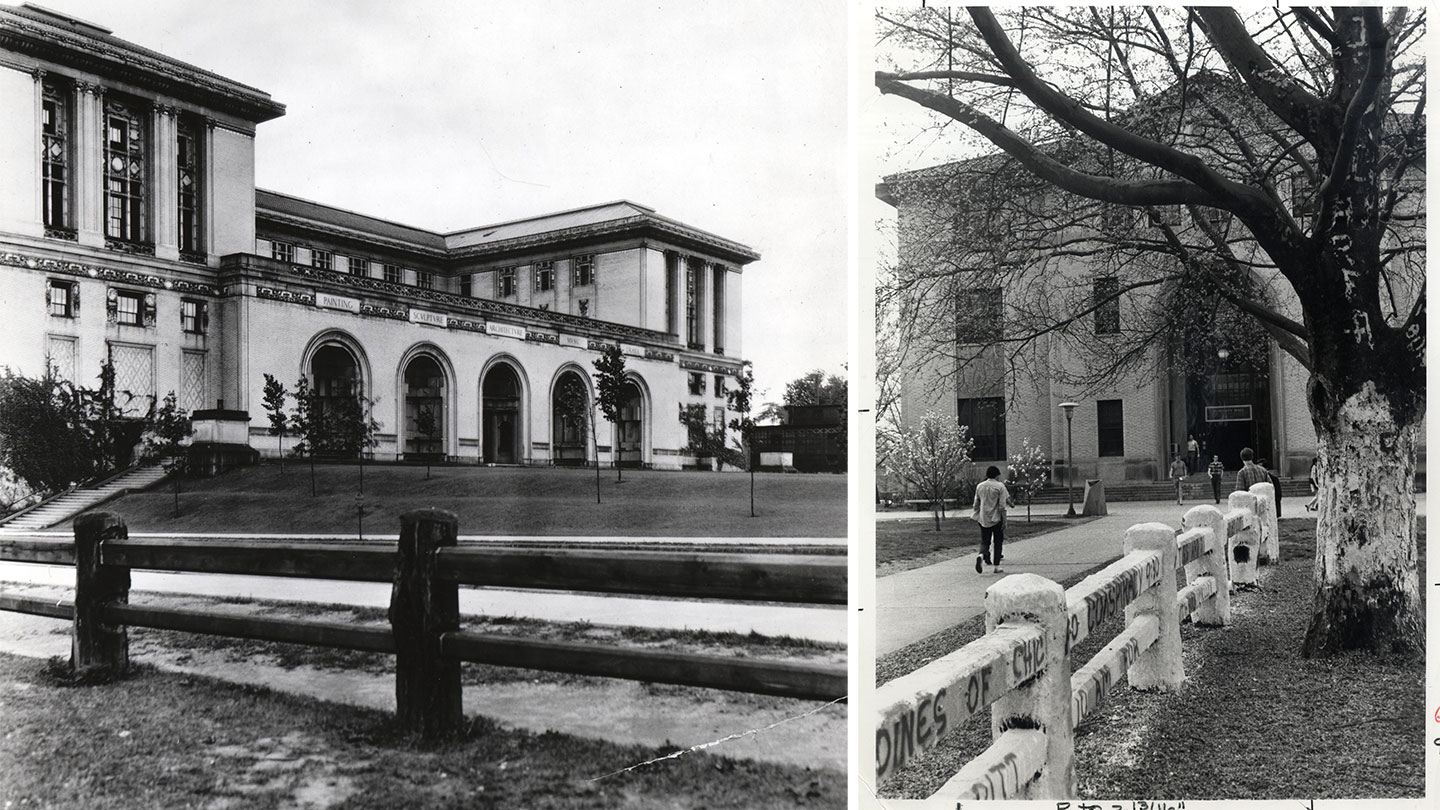

Photos: A selection of archival images from Amanda Ross-Ho’s research

Public Art at Carnegie Mellon University

Both Ross-Ho and Maravilla’s sculptures join CMU’s permanent public art collection alongside the opening of two new buildings this year — a deliberate pairing of art and architecture that reflects CMU’s “Simons Principles.” Established in 2013, the principles incorporate public art into all new construction on campus. Artists are selected with an eye toward the building’s fundamental purpose and the campus communities it serves, ensuring that the public artwork not only enhances the architectural space but also resonates with those who will use it. “Each project is really artist-led,” said Chodos. “In every instance, I’m trying to give the artist enough direction to where there’s an alignment with the overall goals and vision of the building, but open enough to where the artist can lead from there.”

CMU’s commitment to fostering an environment where art is integral to campus life is about more than just beautifying a location. One of the key ways public art serves an academic setting is by aiding students — in particular, students in the School of Art — to understand the world that they’re entering, what paths are available to an artist and educator like Ross-Ho or a professional studio artist like Maravilla. “I think bringing in artists of a certain caliber through the public art on campus helps our students see the role that artists can play,” Chodos explained.

As Maravilla put it, part of the role artists — and public art — can play is to offer an enduring source of inspiration: “Even after I’m gone, I want my work to spark interest in what healing is and what my message has been in the world. Maybe someone sees it and begins their own personal journey.”